A tiny gesture of hope in Detroit

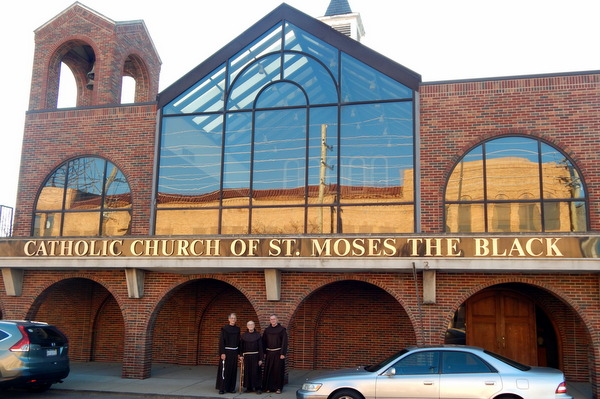

Friars Alex Kratz, Maynard Tetreault, and Louie Zant at St. Moses the Black friary in Detroit

Friars are welcomed by a neighborhood that needs them

~

There are four signs on the building announcing the presence of friars.

“One thing I learned working in evangelization,” says Fr. Alex Kratz, “is to let people know where you are.” So every few yards, there’s a sign marking the site of the newest Franciscan friary in Detroit: St. Moses the Black. The last time anyone lived in this former rectory on Oakman Boulevard was 20 years ago. Since October it’s been home to Alex and fellow friars Br. Louie Zant and Br. Maynard Tetreault.

Across the street

In a city rebounding from its past, the friars are part of a neighborhood that’s been left behind. Next door is a food pantry that sees brisk traffic. On the street in back, eight houses are boarded up or so structurally unsound they’re caving inward. With windows broken or shuttered, nearby factories are lifeless and desolate.

A few blocks away is another sign, this one marking the boundary of Highland Park. It not only has the highest crime rate in Detroit – 46 crimes per 1,000 residents – but one of the highest in America. Here, your chance of becoming a victim of either violent or property crime is one in 22. If poverty has a Ground Zero, this is the place.

For Maynard, Alex and Louie, the natural question is, “Why here?” And just as important, “Why now?”

Abandonment

The “now” part seems like divine providence. “This is the 50th anniversary of the riots in Detroit,” says Maynard, referring to a tsunami of violence that swept the city in 1967, leaving 43 people dead and 2,000 buildings destroyed. For Alex, race and inequity converged in recent, deadly confrontations between African-Americans and police officers. “All of this came crashing into my prayers,” he says.

Food pantry helper Ron Nunn with Pauline Ford & Damita Brooks

In March he suggested the friars expand their Detroit-area presence into an underserved neighborhood that was predominantly black. “I’ve been here [in Detroit] since 1999,” serving as Director of Evangelization for the Archdiocese for eight of those years. “Whenever I drive, I take the highway. I bypass miles and miles of this,” he says, waving an inclusive hand. “I felt a bit conflicted that I kind of avoided this whole area,” including the adjacent city of Highland Park, “which is even poorer than Detroit.”

A quote from a class at St. Bonaventure – “Faith must have social consequences” – nudged Alex forward. “My studies kept echoing in my head,” he says. “Social location is part of our Franciscan charism. When we’re in a location where the poor are, it changes your witness.”

Mark Soehner, former pastor of St. Aloysius in Detroit, knew the area well. During his time as Director of Postulants, “He also worked in this cluster and taught RCIA,” Alex says. “We talked a lot in general” about problems and possibilities. “We say Detroit has suffered ‘demolition by neglect’. We only have a few Catholic parishes in the city. There’s a feeling of abandonment among Catholics in Detroit. Institutionally, the Church has pulled out.”

Spirit at work

Associate Pastor Patrick Gonyeau with Alex, Maynard & Louie

A pastoral letter called “Unleash the Gospel,” released in June by Archbishop Allen Vigneron, was a call to evangelization. “His plan is to have the religious evangelize the city,” Alex says. At St. Moses the Black, “I’d say we’re on the cutting edge of evangelization.” As friars, “It’s right down our alley.”

After the Provincial Council endorsed his plan, “It took some looking and searching” to find the right place. “If I was going to invite friars in, I didn’t want to be in a structurally dangerous building with a slumlord.” That eliminated a number of prospects. Finally, “The Holy Spirit guided me to this,” a rectory attached to St. Moses the Black Church.

The pastor, J.J. Mech, also serves as rector of the nearby Cathedral of the Most Blessed Sacrament and pastor of Our Lady of the Rosary. His associate in all three locations, Patrick Gonyeau, is also Central Regional Coordinator of Evangelization for the Archdiocese of Detroit. The very busy Patrick speaks for the community when he says, “There’s such an excitement about the Franciscans being here.”

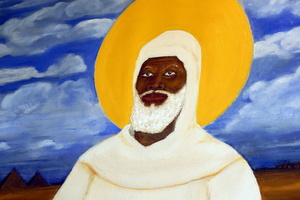

St. Moses the Black

Indeed, “People have been very welcoming,” says Louie, a regular at morning Mass.

“The parish is older, but there are kids in catechism class,” according to Maynard. “There’s always hospitality after Mass. They have a lively liturgy and a great choir.” Now, “All they need is people.”

For Detroit-born Maynard, this was a homecoming. “Our parish [Visitation] was a mile from here. These were my old haunts.” He remembers Oakman Boulevard as “a nice, middle-class neighborhood,” more upscale than his own.

This summer his ministry in Galveston, Texas, ended when the province returned Holy Family Parish to the diocese. “This [Detroit proposal] didn’t really come about until April. I heard about the potential of this place. I think our presence among marginated people is important. I think it is a tiny gesture of hope.”

Cleaning up

Formed by the merger of three parishes, St. Moses the Black spans most of a block on the boulevard. It’s a fortress of a building, with arched doorways and a vaulted atrium that serves as a vestibule and meeting space. Near the main door is an imposing painting of the church’s patron saint, the 4th-century slave who gave up a life of banditry to become a desert monk and an apostle for nonviolence.

Br. Louie at the food pantry

Up the steps and off to the right is the friary, which until recently served as the hub and storage facility for St. Moses the Black Food Pantry. Now the pantry is housed in the former school next door, where Louie is a volunteer.

He visited the future friary after returning from missionary service in Jamaica. “I was just interested in going someplace where I could be useful,” he says, like Pittsburgh or Cincinnati. “Alex asked me if I might be interested in coming to Detroit, interacting with people in neighborhood projects.” Louie recalls his first visit.

To enter the building, “We came through a rolling metal door” that blocked homeless people from sleeping on the steps, turning the rectory into a bunker. Inside, “There were boxes all around. The first floor was used as storage” for the parish food pantry. “It needed some cleaning up,” he says. Despite the clutter, “We saw the possibilities” in the 92-year-old rectory.

“This place hadn’t been lived in in 20 years,” says Maynard, whose eagle eye as Provincial Building Coordinator does not miss much. “When we did the walk-through and saw plaster coming down, we knew it needed some care.” The parish fixed the plumbing and replaced the roof. Electrical work is an ongoing project. Most of the 17 doors would not close, a typical issue as old buildings settle. All of them needed sanding and/or lock repairs.

Looking, listening

By the time he moved here Oct. 2, Louie says, “Things were very liveable.” The furnishings, most donated, have the plain but serviceable look of bygone friaries. The addition of Internet was a must, but TV screens are absent by design.

Fr. Alex with helpers at the food pantry clothing outlet

Slowly but surely, Maynard and Local Minister Louie have whittled the to-do list to a manageable size. Now they’re assessing the needs of their neighbors and quietly making their presence known.

Around here, “People carry a lot of burdens,” Alex says. “Some of them live on their own. One of the things I’ve been thinking of doing is asking people waiting at the food pantry if they’d like to be prayed with.”

As for Maynard, “I’m not putting out my shingle” for sacramental ministry just yet. His goal for this first year, he says, is “to listen”, learn what people need “and what the bishop wants.”

Alex came into this juggling another project, the restoration of St. Joseph Chapel and the Shrine of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Pontiac. It’s also the home of Terra Sancta Pilgrimages, which he co-founded and leads.

At St. Moses the Black, “I think being visible and being in the neighborhood is important,” he says. One day at 6 a.m., “I was praying the rosary on the sidewalk” while wearing his habit. “A young guy was catching a bus for his job at a potato chip factory. He did a double take and said, ‘You’re medieval’. I explained to him what friars are about.”

Maynard is encouraged by what he’s seen. “I was happy to hear about us going into the city. A lot of people are working on a comeback for Detroit,” including a mayor [Mike Duggan] “who has promised to do more for neighborhoods. There are many hopeful signs.”

Four of those signs, lettered in brown, are attached to this building.

This story first appeared in the SJB NewsNotes.

Posted in: Jesus, Missions, Newsletter, Prayer, Saint Francis